Everything is changing, leaving, and returning. There is always a constant transience in this world.

Strange but one sees little of the transience in question ever dramatized in this film. The film promises movement and what we get is stasis. If nothing else, everyone here is trapped in purgatorial states, a state of imprisonment, which makes transience synonymous with escape. Escape, that’s all – and perhaps a dastardly one. Let’s recite their names one by one. Martin, unable to fend for himself, literally hightails it to the loving arms of his parents in the States. Grace sees transience by giving up on her marriage. The line of least resistance. And those who supposedly make the existential transition – the transient ones? The lovers, William and Joan – they do so through violence. Violence also takes another neighbor; they find her all broken like the rag doll that is supposed to stand for her missing younger sister. Sick. And how about the ghosts trapped in this haunted apartment building? This film defines transience in the most perverse terms: A function of flight and defeatism. The frightening part is, it seems done in solemn earnest. As such, one tries to see another film altogether. Another review instead, written before knowledge of those lines about transience – unearned, never made concrete.

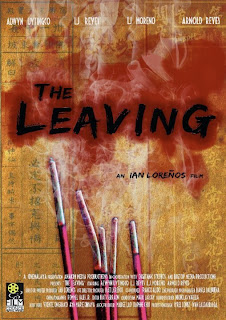

According to popular notions, the Chinese in this country are so clannish and tight-knit in their ethnicity that it's hard to single out anyone of them who is struggling in life. Mention the word Chinese and this immediately conjures lofty and grandiose images of a business tycoon, or a rich, well-connected fat cat, or a kid studying in the most exclusive schools. In Ian Loreños’ The Leaving, one gets to see the other side of the tracks: Tsinoys who are economically vulnerable and subject to moral and human susceptibilities.

But Loreños -- who wears a number of hats as writer, producer and director for this film -- locates his characters almost exclusively within a middle-class spectrum, which short-circuits some of the exercise. Still, in a film set in a haunted apartment building in the enclave of Binondo, it’s a good college try. Perhaps, there aren’t really impoverished Tsinoys around after all.

Three intertwining stories make up The Leaving: subtitled Martin, The Lovers, and The Wife. In Martin, the eponymous character is the scion of a once-wealthy family who have since emigrated to the United States

A nagging feeling of familiarity, however, sours an appreciation of this film. What condemns it is an unbridled wearing of influences on its sleeves. The Leaving is a pastiche of all-too-identifiable sources -- from Asian movies, mostly Hong Kong derivations, particularly Wong Kar-Wai, and still more specifically In the Mood for Love. Read above for the plot toThe Wife. From the very Asiatic color motif – red, all shades of red, curtains, calendars, fruits, dresses, and blood, copious blood – to suspiciously familiar shot compositions to the presence of ghosts recruited from Asian horror flicks, Nakata’s The Ring among others, this film is like a shameless collage that would put Picasso and Braque to shame.

No comments:

Post a Comment